Music Nomenclature

Even though you are new to this, and the ukulele is your first instrument, I guess you know that music is formed by a succession of notes, as if they were letters forming a text. In western culture, this musical “alphabet” is made of 12 notes. Yes, you heard me well, from J.S Bach to Iron Maiden, it’s all based on 12 unique notes.

We can trot these notes out, thanks to Mary Poppins :

C, D, E, F, G, A, B

Wait a minute – you’re probably asking “Didn’t you say 12 notes? I only see 7 here…”

That’s right. What Julie Andrews used to sing was actually a C major scale, formed by 7 notes (like all major scales, and many other scales). These seven notes are also known as the natural notes. Actually, what’s missing is a series of notes placed in between some of them. This is what we refer to as semitones. A semitone is in the middle of two consecutive notes which are one tone away from one another (for example between C and D), i.e 2 semitones correspond to a full tone. We can’t further divide a semitone, we are facing the “elementary particle” of music (at least in western music).

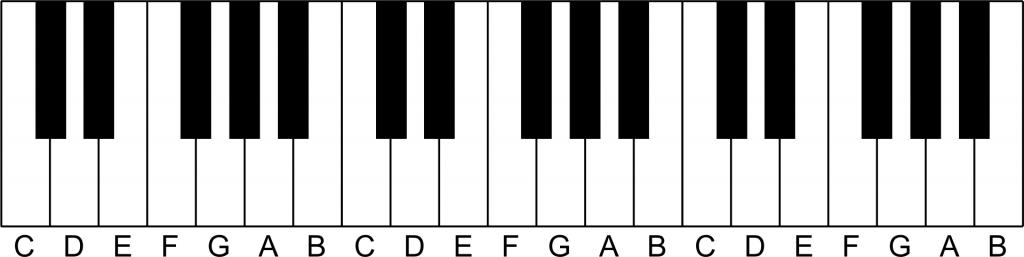

Applied to the piano, the white keys are separated by one tone (90% true, you’ll see why later) The black keys located in between 2 white keys are semitones. On a guitar, each fret is a semitone, therefore every two frets we have a full tone. On the ukulele, the same thing occurs.

Let’s take an example. If we play the third string open on the uke, we know it is a C (in standard tuning). If we pluck on the second fret, we have moved 2 semitones forward, which is the same as a full tone. Therefore, according to Mrs. Poppins’s song we will be playing a D. If we move another 2 frets forward, we will have a E… easy, isn’t it? All right, so now we are going to fill in the 5 blanks left, so we get the 12 notes I mentioned.

Piano Keyboard with notes

Photo by Metoc (CC BY-SA 2.5 – original)

Lets go back to the piano, and we are going to focus only on the black keys:

We can see that between some of the white keys (tones), there is no black key (semitone). That’s correct, specifically between the E and F notes, and between B and C, we have no semitone. That’s why we have 12 notes (7 tones and 5 semitones) and not 14 notes (7 tones and 7 semitones). Therefore, between the E and F notes, and between B and C, we will always have a semitone, straight. Always, always. I promise.

You’re probably fine with that, yet still wondering about these 5 semitones… how are they called? Well, this question is more complicated as it may seem. If we were strict, we wouldn’t be able to “name” them unless we know the “scale”… But, for now, and in order to keep it simple, let me introduce sharps (designated by #) and flats (designated by ♭), known in music as alterations.

A sharp note indicates that we need to move one semitone forward from the base note. It means that the note will be altered to end up being one semitone higher (on a piano, this means moving towards the right). For example, a C# will be just one semitone higher than a C. On the contrary, a flat indicates that we need to lower the note by one semitone, i.e, make it a semitone lower (on the piano, towards the left). For example, a E♭ is one semitone lower than a E.

Now you can fill in the 12 notes that form our “alphabet”, bearing in mind that, as we said, E and F are separated by a semitone, so we can’t put any sharp note between them, same thing between B and C. For this example, we are going to use sharp notes only:

C C♯ D D♯ E F F♯ G G♯ A A♯ B

(the following note would be a C again, one octave higher than the first one)

If we just use flat notes:

C D♭ D E♭ E F G♭ G A♭ A B♭ B

As we compare these 2 “scales” (the one with “sharps”, and the one with “flats”), and because we’re pretty smart, we’ll notice that a sharp and a flat are the same, it’s just a matter of having the previous note as a reference and putting it one semitone higher (sharp notes), or taking the next note and lowering it by one semitone (flat notes). You will probably be asking: “Why do we need two words to refer to the same note?” Because, depending on the harmony, a specific sound will have one name or another. For now, stick to that, and to the fact that within a same scale or key signature (a set of notes), we will never mix sharps and flats, neither will we repeat the same note (we can’t have a A and a A#).

There are other alterations, apart from sharp and flat notes. These are natural signs, double sharps and double flats, and so on, though you will not use them at all for now if you don’t further study music theory and harmony. In addition, other alterations such as quarter tone flats, quarter tone sharps, three quarter tones flat etc can be found exclusively in non-western music, where a semitone can be divided in smaller parts.

Featured image by Brandon Giesbrecht (CC BY 2.0 – original)

I see your website is in the same niche like my weblog.

Do you allow guest posts? I can write high quality & unique content

for you. Let me know if you are interested.

If Uke-related, why not.